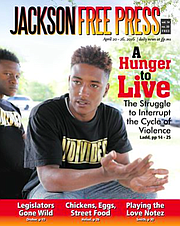

Terun Moore stands outside an abandoned house in the Washington Addition, one of three Jackson neighborhoods where a new credible-messenger and violence-interruption program aims to counsel residents at risk of committing violence. Photo by Seyma Bayram

It was a warm day, so Terun Moore slung the Dallas Cowboys starter coat his uncle gave him over his shoulder as he stepped off the school bus. He and two friends were walking toward his grandmother's house in the Virden Addition neighborhood of Jackson in the fall of 1993 when a car approached.

In it were two young men, no older than 17 or 18. Moore, who was 12, had not seen them before, but he agreed to help when they asked for directions.

That is when one of them jumped out and grabbed Moore's favorite jacket. He got back into the car, and the pair sped off.

Moore was hurt and felt weak as a result of the incident. It was the first time anyone had stolen from him. He did not want to feel that way again.

Not long after the theft, Moore joined a local version of the Gangster Disciples, a street gang that originated in Chicago in the late 1960s. Moore's early gang-related crimes were participating in a string of robberies. Then when he was 17, Moore killed a man during an armed robbery in Jackson. A judge then sentenced Moore to life in prison without parole.

'Trying to Be a Bright Light'

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that sentencing minors to life without parole was unconstitutional. After spending 19-and-a-half years behind bars, Moore came home in 2017.

Since Moore left prison, he has used his own criminal history to mentor young people, hoping to help them make better decisions. "I don't want to land back in prison," Moore told the Jackson Free Press recently. "I want to help somebody not go to prison who may be feeling the same things I was feeling when I was young, just trying to belong to something and really not even knowing what it is about it."

In 2017, Moore co-founded the People's Advocacy Institute, a grass-roots organization that pushes for change in criminal justice and electoral policy and provides legal support, with his childhood friend, attorney and activist Rukia Lumumba. Last year, he and Lumumba decided to create a credible-messenger and violence-interruption initiative to tackle the roots of violence in Jackson. Lumumba had already been involved in similar initiatives in Washington, D.C., and New York City.

Credible messengers, many of whom have been through the criminal-justice system, enter into communities to mentor and discourage at-risk individuals from participating in criminal activity.

Soon, Moore and Lumumba recruited Benny Ivey, another formerly incarcerated man and former white gang leader from Jackson, who wanted to do similar work to help others avoid the crime cycle. It was good timing: In 2018, Jackson saw its highest homicide rate in years, with 84 murders—a 31% increase over the previous year.

By January 2019, the trio started holding community meetings and raising funds for the new program to add to $150,000 in seed money from FWD.us, a criminal-justice advocacy organization funded by the tech industry. They are preparing a recommendations report that will detail what a credible-messenger and violence-interruption program should look like in Jackson. They hope to launch officially in January 2020, with Moore and Ivey serving as full-time messengers as they recruit more community members.

"I'm trying to be a bright light," Moore said while walking through the Washington Addition, just south of Jackson State University. The team plans to target the historic middle-class neighborhood that was active during the Civil Rights Movement, but has since struggled with poverty and high crime, much of it owing to a combination of disinvestment and the ongoing repercussions of the 1980s crack-cocaine epidemic. An Esri demographics report found that the predominantly black neighborhood has an 11.7% unemployment rate and a $17,963 median household income.

The Virden Addition further north and parts of south Jackson are also on the initial list of target areas for the credible-messenger program.

The Virus of Violence

Desmeon Thomas is a Jackson native who has used a wheelchair since a 2002 shooting during a car-jacking that left him paralyzed. He attended a community meeting Moore and the credible-messenger team hosted at the COFO Civil Rights Education Center on Nov. 19.

There, Thomas said mentors must feel authentic to those they are trying to reach in order to make a difference.

"Me being a person with paralysis, can't anybody just come tell me how to be a person with a spinal-cord injury or how to live that lifestyle," Thomas said. "It's got to be someone with the same diagnosis who experienced it before I did."

To Thomas, the credible-messenger model makes sense for Jackson. "[T]hey lived that lifestyle, and they walked that walk, so when we're going out and talking to the youth," he said, "it's relatable and they can understand that the only reason why we are there to speak with them is because we care."

The model requires that the messengers—who themselves have been either victims of crimes or perpetrators, often both—come from the same communities and similar circumstances as those they are mentoring. Therein lies their credibility and distinction from traditional counselors, whose advice may not resonate with the people they most need to reach.

"We feel like we're the people that can help here in the community because we helped hurt it, a little bit," Moore said, emphasizing Thomas' point. "It was our examples of wrongdoing that caused other people to go that way, too. ... We got some beautiful people here, but (violence) is hurting our city," he said.

In Jackson, the plan is to combine credible messaging with violence interruption, following former World Health Organization epidemiologist Gary Slutkin's successful "Cure Violence" model. Slutkin views violence like an epidemic. Curing violence requires identifying people with the disease, treating those at highest risk for it, and changing behaviors and social attitudes around the disease, he believes.

Trained, paid "violence interrupters" carry out the "Cure Violence" work through on-the-ground counseling, working to literally interrupt violence before it occurs, especially in the aftermath of a violent act, which may lead to further retaliatory actions, causing the violence to spread like a virus. They do this work unarmed.

Studies have shown that the model works when interrupters are properly trained. New York saw a 63% reduction in shootings in the South Bronx, and a 50% decrease in gun-related injuries in East New York. A 2012 joint study from the Centers for Disease Control and Johns Hopkins University found that violence interruption in four Baltimore communities led to a 56% reduction in killings there.

Lumumba said that once the initiative releases its recommendations report, it will accept applications from community members who want to deliver services aligned with their skill sets. The program will offer a series of trainings on topics such restorative justice and positive youth development, as well as training for mentors.

'Just Like Any Disease'

Gun violence is personal for Rukia Lumumba, the sister of Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba. Their older brother was shot in the head in Jackson when she was a little girl. He survived the shooting, but is paralyzed as a result of the incident.

For Rukia Lumumba, Slutkin's "Cure Violence" model is a way to create healthier communities. The goal, she told the Jackson Free Press, is to reflect on and use the resources available locally, but to also build them up, with the violence-interruption program further equipping communities with important skills.

As a lawyer, Lumumba had access to trauma-informed care, social resilience and harm-reduction trainings. These skills, she believes now, should be accessible to all communities as prevention tools.

"Another big component of this is to be able to offer those trainings to the community, just on a consistent basis," she said in an interview. " ... How to engage with dignity when someone is having a psychotic episode—how are you able to engage with that person to not harm yourself and then not harm them? ... How can (the harm-reduction) model help to change how we deal with our loved ones who are suffering with drug addiction?"

Lumumba added that residents already do a lot of the work of credible messengers, even if they do not have formal training. The pastor of Rosemont Missionary Baptist Church in Jackson, for example, has led neighborhood clean-up and watch efforts, built a community garden, and more.

"We're not creating anything new," Lumumba said. "We're just providing more opportunities for more people to take up that space."

It is also a way to build systemic prevention and actually stop violence from multiplying like a virus. In 2016, Slutkin told the Jackson Free Press about a study demonstrating that the "Cure Violence" approach had a 100% success rate in preventing retaliation.

"I don't know if it's 10 or 70 events that wouldn't happen" following one successful intervention, Slutkin said, because each prevented murder chips away at the cycle of revenge and further harm.

The mayor has on many occasions said that it is impossible to out-police crime, which is especially true for homicide.

"We have more police than any other country in the world, we have more people incarcerated than any other country in the world, yet and still, we have more crime than any other country in the world. Therefore, there has to be another dynamic that we may be missing," he told the Jackson Free Press this month.

Violence is "just like any disease," the mayor said. "You need to kill it. You need to know what is the proper treatment for it."

Affording the Solution

Slutkin emphasized to the Jackson Free Press that a trained, dedicated, full-time staff is necessary for the model to work and actually prevent violence. He made it clear that two or three interrupters trying to mentor a few young people is not enough to stop viral violence. In Jackson and many cities, funding remains the biggest obstacle to implementing a sustainable program.

In its early years, the Chicago pilot of Cure Violence averaged about $240,000 in yearly funding, but additional contributions from federal and state governments and philanthropic organizations grew its budget to $6.2 million in 2005 and $9.6 million in 2006. Earlier this fall, a St. Louis, Mo., alderman introduced a bill to grant $8 million, over three years, to start a Cure Violence program there. The board approved $5 million. Jackson's population is roughly half of St. Louis, and its murder rate is slightly lower.

This year, for the first time, the City of Jackson is giving $102,018 to the credible-messenger and violence-interruption program for 2020.

By press time, the City of Jackson could not detail how the funds will be used, but about half of that amount is intended as a salary and benefits for a full-time person to oversee the program in Jackson.

The mayor said he is excited about supporting the program. "We think that if you don't invest time and invest money in terms of addressing the root causes of criminal activity or the breakdown of relationships, then you're always chasing behind problems," he told the Jackson Free Press.

"What we find is that the community is closest to the solution, long before the police or the leaders or politicians learn of something that's taken place in the community," he continued.

The City can support the work of violence interrupters not only through funding but also by directing individuals and communities to the services they may need, such as employment and educational opportunities, job training and food access.

The mayor said the City cannot afford much funding for the program, but he says that if Jackson residents see the potential of the credible-messenger program, they can take part in the participatory budgeting process to increase funding for it.

Distancing from Police

The Jackson Police Department may have been part of the initial announcement of the credible-messenger program in late 2018, but experts say the violence-interrupter model can only work without law-enforcement interference.

In order to maintain credibility, messengers and interrupters must not be viewed as working together with police, or worse, as snitches, due to the historically tense relationship between police and over-policed communities even in cities with majority-black police departments like Jackson.

The Rise of America's White Gangs

Donna Ladd reports for The Guardian on the largely ignored rise of white gangs in America, and how they're treated differently from black and Latino gangs. Photo: Imani Khayyam

Jackson Police Chief James Davis did not respond to a request for an interview by press time, but the mayor said local law enforcement understand this delicate relationship. "Our police department—many of the leaders within our police department—have been educated on the distance, the proper distance, that they need to provide," the mayor said. "They don't need to be engaged with the messengers, because the messengers have to be able to go into spaces where they need to have the (sincere) trust of the community."

JPD Deputy Chief Deric Hearn, who was present at the Nov. 19 meeting, says law enforcement must approach the community from a place of love.

"A lot of people in Jackson, especially young people, they just need some guidance, they need some attention," he said.

"They might not have had a father, they might not have a mother ... but the strong is supposed to pick up for the weak, and I think that every law enforcement ought to have a commitment to serve, not just arrest. ... If you're there to serve, you can prevent a whole lot that can happen."

Rather than a community outsourcing its problems to law enforcement, the credible-messenger and violence-interruption initiative aims to equip communities with resources so that they can take care of each other. This includes creating spaces for after-school activities, in cleaning up neighborhoods, in improving education access, and alleviating poverty and making residents feel safe, Moore said, so that people do not resort to a life of crime to survive.

"We just need somewhere where people can go and be free," he said, adding that his biggest wish is for "the community to have love again."

"That's like our main objective, trying to love on those folks and get these folks involved and love on themselves," Moore said. "People need to be met where they're at. Everybody ain't going to grow up the same way or have the same morals or values, but that doesn't mean they're not valuable."

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article stated that murders in Jackson increased by 25% from 2017 to 2018, but they actually increased by 31%. We regret the error.

Donna Ladd contributed to this report. To read more about the "Cure Violence" strategy, see jacksonfreepress.com/hungertolive. Also see the JFP's solutions-based "Preventing Violence" archive here.

Follow City Reporter Seyma Bayram on Twitter @SeymaBayram0. Send story tips to seyma@jacksonfreepress.com.

More like this story

- Former Criminals Training to Stop Violence in Jackson with $150,000 Grant

- Ending Viral Violence: Strong Arms of Jackson Holds Rally Against Gun Crime

- Strong Arms of JXN to Hold Non-Violence Event in Grove Park

- Mayor Lumumba: Violence Prevention Must Take Into Account Poverty and Gun Laws

- Due to Murder Spike, Lumumba Pledges More Surveillance, Prevention Efforts

More stories by this author

- City Announces Robinson Road Repaving Project; Stay-At-Home Order Still in Effect

- City of Jackson Sues Canadian National Railway Over Blocked Railroad Underpass

- Mayor Lumumba Revises, Extends Jackson Stay-at-Home Order

- Mississippi Justice Institute Sues Mayor Lumumba for Open-Carry Order

- Jackson Attorney with COVID: ‘A False Sense of Protection Here’

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.